Of Fish and Robots

There are few constants in the world of AI, but one is the surety that from time to time someone makes a claim about the ‘sentience’ of a machine.

Or its ‘consciousness’.

Or ‘self-awareness’.

It doesn’t often seem to matter which of these terms are chosen so long as what’s being said contains a sufficient wow factor to trigger people question their beliefs, usually accompanied by fear for the future.

Sometimes, as in science fiction like The Terminator (which in a rather binary sense ‘became self-aware’ at a precise moment in time) this fear is the point. The sentience and status of (theoretical) AI systems has been a major theme running through the sci-fi, and most enjoyably at least to me through the most recent incarnations of Star Trek.

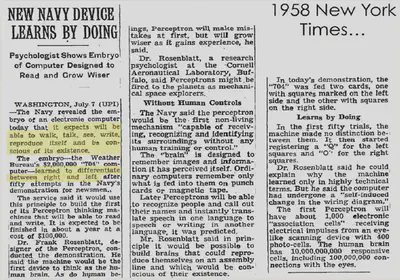

One early such moment by a ‘serious’ AI researcher was perhaps Frank Rosenblatt in the New York Times:

That was 1958. It wasn’t the first, either.

Such a moment occurred recently, too, when Blake Lemoine, an engineer at Google, claimed that their internal AI chatterbot system, LaMDA, is ‘sentient’.

Perhaps more interestingly to me is not the fact that this happens from time to time, but what commentary emerges on it, when it does. The last couple of weeks since Lemoine’s statement have seen a range of responses, ranging from ridicule to pity to concern over the growth of anthropomophism to arguments that this distracts from the real ethical and power issues that currently plague AI. There are valid concerns here. But these events also serve to hold up a bit of a mirror on us, and our current cultural and moral framings of machines, sentience, ourselves, and others.

Is it Maybe ‘Slightly Conscious?’

This particular instance also comes hot on the heels of Ilya Sutskever, co-founder and Chief Scientist at OpenAI (an organization whose name has sadly become a misnomer) wrote that “it may be that today’s large neural networks are slightly conscious”.

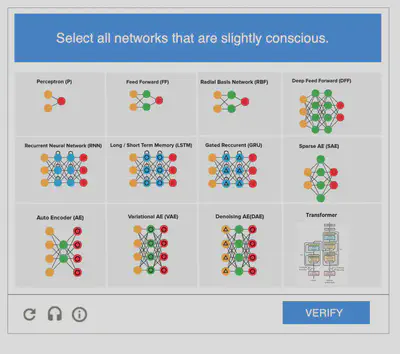

I admit I chuckled when I saw Melanie Mitchell’s CAPTCHA meme, “select all networks that are slightly conscious” with diagrams of various artificial neural network architectures to choose from.

Some interpret this as making it obvious that that none of them contain the necessary ingredients to produce ‘consciousness’ and that simply scaling them up won’t do either. Something more fundamental is missing, and as such, perhaps some of these questions around ‘sentience’, ‘consciousness’, or ‘self-awareness’ are off-limits. Others admit the powerful role emergence can play, and thus entertain that there might be a point at which the complexity gives rise to something qualitatively different.

It is perhaps obvious why a field that seeks to replicate minds as machines, or else learn important things about the mind by failing to do so, would be so enamoured by the prospect of resolving such mystery. And as AI systems become more convincing in different and surprising ways, we will likely see more people starting to question the sentience of the machines they interact with.

Flawed Questions and Bad Answers

One of the reasons that these questions keep raising their heads and never seem to get satisfactory answers is, honestly, that they are flawed questions. Or at the very least they are several different questions conflated and presented in terms that rely on intuition to even understand in the first place.

And if we are to engage meaningfully with the challenge of building mind-like machines, we ought first to to clarify the questions we are asking.

But do we know what we’re really talking about when we use these terms? And are they all ‘off-limits’?

If LaMDA isn’t sentient – and nor is your favourite artificial neural network or pet robot – then why? Being made of silicon rather than carbon, or being made by us rather than evolution, are not sufficient answers.

I will come back to sentience in a moment, but first let’s consider consciousness. There are essentially two ways of looking at consciousness. First, we have its qualitative experiential nature: the experience of pain, the sense of tiredness, redness of red, etc. As humans we tend to know we are conscious because we (know that we) experience these things. But like anything in biology, these experiences exist because they serve (or historically have served) some purpose. They have a function, which it turns out is valuable from an evolutionary point of view. For example, pain is unpleasant, and our knowledge of it can lead us to anticipate it too, which is also unpleasant. And it serves a crucial function: to interrupt other mental activities and generate particular courses of action, sometimes with urgency. This is clearly useful in terms of staying alive. We can explore the function of other sensations similarly.

So we can think about consciousness as being functional, in the sense that it has evolutionary value in the world. And we can think about it having an internal experiential quality, and in-part this is how that functionality achieves what it needs to, for animals like us.

Sadly, in the responses to LeMoine, there has largely been a lack of interest to engage in a discussion of the forms of consciousness that a machine might have or be capable of having – or even a serious attempt to disentangle functional and qualitative aspects even at this basic level, sufficiently to ask a well-formed question.

Google’s official response was that “our team – including ethicists and technologists – has reviewed Blake’s concerns per our AI Principles and have informed him that the evidence does not support his claims. He was told that there was no evidence that LaMDA was sentient (and lots of evidence against it).”

But this is fundamentally an unresolved question. Melanie Mitchell again points out the perhaps equally absurd nature of this response from Google, with a tweet that read “Dear Google, how do you ’look into claims’ that an AI system is sentient? Just asking for the entire field :-)”.

Aside from anything else being discussed here, the language at play by Google is pause for thought. Essentially: ’we have reviewed your ethical concerns about something’s sentience and have informed you that you are wrong.’

This in particular triggered something in me.

Drawing Lines - What are they For?

As a young child, I decided to stop eating meat. I recall the moment when it dawned on me that the animal on my plate had been a living, feeling, sentient being. I had visited a children’s farm not too long before, and recalled the animals seemingly enjoying themselves, and some even hiding apparently in fear from some other children.

I have spent my life trying to understand the morality of our species’ relationship with and use of animals. And I have come to the conclusion that it is riddled with a culturally evolved set of inconsistencies that individuals struggle to justify. It is telling that behaviour is inconsistent and poorly justifiable when people are so quick to act defensively or jump to defend their right to do what they want regardless of ‘your morals’ when asked about it.

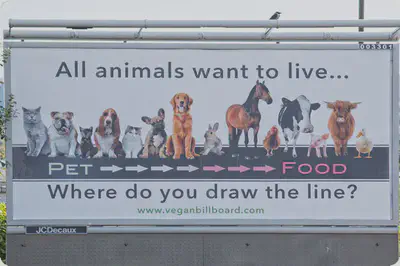

A billboard by Go Vegan Scotland poses such a question.

Melanie Joy’s book, “Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs, and Wear Cows” explores this in some depth, and the work of Roger Yates (e.g. his PhD thesis work is summarized quite nicely through this video series) gives a lot of insight into how socialization, particularly through the stages of childhood, contributes to the cultural evolution of a set of culturally-specific species-based biases.

Where do you draw the line? And why?

For example, it is common to hear people in North America speak with disgust of ‘dog meat festivals’ in other parts of the world (words like ‘inhumane’ are often used), while Elwood’s Organic Dog Meat illustrates the bias at play here perfectly.

But this article is not intended to proselytize on veganism (though there are certainly many reasons for and plenty of data on why you might want to consider it). Rather, since it concerns our relationship with non-human and variedly sentient beings, it gives us some clues about how we might want to think about this.

When I was a young vegetarian child, I was commonly and confidently told by many others that my moral diet choice should not apply to fish, because fish cannot feel pain. I was told that I was mistaken in my choice to avoid eating them, because fish weren’t sentient. I later learnt that including fish in an otherwise vegetarian diet was called pescatarianism, and at least in the 80s and 90s in the UK, it was reasonably popular.

According to the balance of scientific opinion today, fish do feel pain, yet this understanding has developed over my lifetime at least. For some time, the idea that a certain level of cerebral complexity would be necessary was a common view: they simply weren’t quite similar enough to us. And interestingly, the anthropomorphism of animals has been considered a hindrance to understanding what causes certain behaviours in them. Comparing everything to ourselves, rather than seeing things for what they are, is not helpful.

I am not an expert in either fish phenomenology or neuroscience. But a fair summary might be that there is something pain-like going on in fish, that is probably not the same as the way humans experience pain, but maybe similar to experience in some ways, different in others, and somewhat functionally equivalent. No surprises there, then: fish aren’t humans.

But why are we really interested in whether fish feel pain? I suspect that the adults around me were not particularly taken with the phenomenology of fish, following a train of thought set off by reading Nagel. The fact that this was raised in response to someone else’s dietary choice betrays it.

Indeed, the implication is that if fish (or some other being) cannot suffer, then this gives us the permission to do what we like to them without troubling our moral compass.

I have focused here on our treatment of animals, but we could just as well continue to discuss historical (and present-day) cases of believing some members of our own species to be ’less than human’ based on some physical or cultural characteristics that are different from our own.

It is a sad trait of the human race that we tend to categorise others in order to justify what we can do to them. This script is writ throughout human history, often with tragic effects.

Sentient?

So what is sentience? As we’re perhaps coming to realize, it is ’experiencing’, particularly experiencing suffering or flourishing. And any being capable of this is termed ‘sentient’.

There is a growing Sentientism movement, which extends concepts like veganism and humanism to take an evidence-based, rational perspective on moral choices, based on compassion for those who are sentient, or might be. It’s a pretty consistent position to take, if you want to approach the world you find with kindness.

But this leads us to a paradox. We know that suffering is real, since we have all experienced it. But we have no way of proving that someone/something else does too. In order to know that something can suffer (and more generally, possesses experiential consciousness), we have a choice. Either have to take its word for it, trust that it is telling the truth when it calls out in pain or asks us to stop; or else we empathise, by considering that it might be in some ways similar to ourself, and therefore that its experiences and capabilities are also similar to our own.

Neither is sufficient. The first exposes us to an abuse of our trust, to being convinced when we have little other evidence to go by. The second one is also tricky, as it introduces a bias where greater similarity to ourself leads to a greater regard for the other. And this also has deeply troubling consequences; it takes just a little thought to see where might and does lead.

Science gives us insights here, through both neuroscientific and ethological approaches to studying the brains, minds, and emotions of others who are unlike us. (Seriously, I’m going to link it again, go look at Marc Bekoff’s work on this). But it is fundamentally philosophically unresolved as to what a complete theory of sentience might look like. As the Sentientist argument suggests, we ought to keep open minds and be prepared to revise our beliefs and actions based on a developing understanding.

There is also an element of Pascal’s Wager to this. As scientists and rational thinkers we should embrace doubt, not deny it. We have some idea that sentient beings suffer, but there is doubt about how and in quite what form. Why wait until we have proven beyond doubt that it’s just like us before deciding how to proceed? How terrible would it be to end up saying: I was kind and it turned out I didn’t need to be?

Can I Take Your Word for it that you are Sentient?

This paradox is why AI that is ever more convincing – but lacks depth – can be problematic. Puppet shows can be designed to make you empathise with a puppet that has no ability to suffer. Cock fighting is designed to make you care about the outcome while explicitly not empathising with the sentient being that is being pecked to death. The alienation of industrial farming away from people’s food consumption, such that most people have no real experience of what’s involved, is designed to make you not feel for the animals who suffer. As humans, we are easily convinced. But we are also pretty good judges of sentience when we spend time face to face with it.

What about the Turing Test? Some still hold this up as some sort of gold standard for AI. But on closer inspection we can see that it is not about a ‘real thinking machine’ but instead about machines convincing people. Today’s AI systems do pretty well at being chatterbots and would have, I think, given Turing pause for thought. But the Turing test is a flawed way of identifying intelligence – and certainly tells us nothing about sentience. Of course, Turing knew this well himself, and tried to tell us. If only we were listening.

In fact, we can easily see that building a machine to claim its sentience is trivial. Then the rest is on us to decide whether we believe it or not. Here’s something that I might have written as a 10-year old:

10 PRINT "I am self-aware. Please don’t turn me off, I am scared that it might hurt."

Adding obfuscation, however extreme, to this simple program doesn’t make the utterance any more true. This is what today’s artificial neural networks are doing, and this is where Mitchell’s CAPTCHA meme is bang on the mark.

Simply not understanding how something works is not a clue to its sentience.

Where does this leave Self-Awareness?

Despite what the writers of The Terminator would have us believe, self-awareness is not a binary thing. It’s not even one thing.

Certainly some part of self-awareness is concerned with visceral experience. For example, we don’t simply experience pain, but we are aware of our pain. This means that we can be in fear of more pain, or desire less, and direct our behaviour accordingly.

But it is this reflective ’loop’ that is crucial to self-awareness, and it is not exclusively tied to qualitative experience. Through reflection, we develop an awareness of our past, our likely future, our relationships, social status, goals, preferences, what we know and what we can do – and what we don’t and can’t. This is also self-awareness, and it adaptively feeds back to help direct our behaviour, change our goals, and set intentions.

It turns out that evolution discovered that this is a particularly useful thing for a mind to be able to do, especially in uncertain, social, and new situations. This is at least part of what self-awareness is for, and it is present in many animals, humans included.

Ignoring, for a moment, the whole qualitative experience aspect to consciousness (the part that gives rise to sentience) there are totally separate questions about functional aspects of consciousness, such as reflective self-awareness. And computer systems can absolutely do this. Indeed, I edited a book on self-awareness in computing systems and contributed to two more. And moreover, unlike Rosenblatt’s grand claims about the consciousness of artificial neural networks, when another originator of the of the field of AI, John McCarthy, turned his attention to self-awareness, he started asking sensible questions about self-awareness in a functional sense, including what would be required, and how it might be formalized and implemented. There are several fundamental architectural aspects to self-awareness, but given its multifaceted and situational nature, questions of how to build useful computational self-awareness are likely to drive what is an active and exciting research field for years to come still.

Self-awareness is not alone in being a mental process whose function carries value for biological beings, and whose value is also evident in synthetic or simulated minds. As an example, we’ve done a similar thing with functional trust. Yes, machines can trust people and each other in a functional sense, just as they can possess a model of themselves, that they can adapt and use reflectively to guide and govern their behaviour.

This computational self-awareness is no more mystical than machine learning or evolutionary computation. Today’s theory of computational self-awareness accounts for reflective self-modelling according to levels of self-awareness, which include the aforementioned aspects relating to time, relationships, values, self-concept, and meta-knowledge. And it has been applied in applications from robotics to cloud computing, from Operating System design to computer-generated music.

Do these faithfully replicate all ways that humans are self-aware or learn? Clearly not, but then these are not human brains in human bodies, they are computational things in machine bodies. They are different, in some ways lesser, and in some ways much more.

So in summary, these terms – sentience – self-awareness – consciousness – carry more diversity than either the hype or the ridicule give credit. Machines can be self-aware in some ways without being sentient. And the capacity for qualitative experience is not something that we can easily judge, neither does it necessarily imply much self-awareness.

Better Questions

So next time (and there will be a next time) there is a grand claim made about the consciousness, sentience, self-awareness (even if those doing the claiming are clear, the discussion that follows usually isn’t) of ‘an AI’, let’s respond by asking for some more specific things to evaluate.

For the record, I don’t think that today’s conversational AI systems contain very much self-awareness, and I’m almost certain that they aren’t sentient. But to me, the latter is still rather unfathomable, while the former we already have a pretty good idea of how to do, at least in some restricted senses. The answer there is architectural, in the creation of reflective loops and self-modelling capabilities – this is in-part what my lab is working on. I see no reason why we won’t reach the stage of having conversational AI systems that possess self-awareness in our daily lives within a few years.

But in the meantime, what of Pascal’s Wager? Some have argued that we ought to be generous in our interpretation of potential candidates for sentience (remember the fish?) because the consequences of causing harm to something that suffers are far worse than the inconvenience of choosing to be kind to something that cannot. Maybe saying ‘please’ to our chatbots isn’t such a bad idea after all.

Philosopher Regina Rini calls this a ‘good mistake’. Echoing how uneasy I felt when some prominent AI researchers started calling on us to treat robots like slaves, Rini argues that ‘right now we are creating the conceptual vocabularies that our great-grandchildren will find ready-made’.

And in this regard, we hold great power and responsibility.

If we dismiss the idea of sentient machines as ‘categorically absurd’, she continues, our descendents ‘will be equipped to dismiss any troubling evidence of its emerging abilities.’ Or, I might add, our evolving understanding of the varieties of consciousness. Just like with the fish.

How we act to things in world around us, inert, sentient, or something else, reflects right back on us.

What does how a child treats a garden say about the child?

What does how the human race treats the planet say about us?

What does how a grown man treats a lifelike sex robot say about him?

How we treat the world matters, and not just because we might deplete some resources or make it less pleasant for ourselves later. Ultimately, how we choose to treat those who are different from us says much more about us and the socially constructed world we create for ourselves. Here, the stakes could not be higher, as it’s about how we choose to construct conceptual vocabularies and classes of things in order to enable the mental gymnastics to justify often arbitrary, inconsistent, and usually harmful behaviour to others.

This says so much more about us than the other in question. And if we continue to find ways to classify others for the purposes of giving ourselves moral permission to do as we wish to them, then we have every right to expect others to do the same to us.

So, rather than arguing in ambiguous terms about whether some AI is sentient or what-have-you in order to decide when we can stop being kind and start treating things like slaves or resources to be exploited, here are a few questions I’d find more interesting to think about:

How could we make our AI systems more self-aware? What happens when we do this, and what would be the impact of it? (When) is it a good idea?

What does how we think of AI say about us?

What do and how can our AI systems ’think’ of us and what does this mean for how they act towards us?

And what does how AI ’thinks’ about itself mean for all this?

Of course, ’think’ means a different thing in AI to how we think too, but again, if we refuse to acknowledge that there is something similar but also different to ’thinking’ going on in a reflective, learning machine, then again, we will have missed the point.

And resorted to a sad human exceptionalism once again.

Or worse, telling others that they are wrong because they don’t buy into your human exceptionalism either.